1. Introduction

2. What is stock photography?

3. Why use stock photos?

4. What can I use stock photos for?

5. Where can I buy stock photos?

6. How to search for stock photos?

7. How do I know if a picture is right for me?

8. What’s the difference between royalty-free (RF) and rights-managed (RM)?

9. Do I need a commercial or an editorial licence?

10. What is a model release and do I need one?

11. What is a property release and do I need one?

12. How does pricing work with stock photos?

13. How can I get the most out of Alamy?

14. How should I store my stock photos?

15. What file format do I need?

16. What file size do I need?

17. How do I change my file size?

Introduction

Stock photography has been on a long journey since its inception in 1936 with the Bettmann Archive. The founder, Otto Bettmann, started with a personal collection of 15,000 photos. Nearly a century on, the industry has swelled into a behemoth with hundreds of millions of images to choose from. It even survived and thrived through the advent of digital photography. But there’s still a lot of confusion when it comes to buying and using stock photos. What are they? Should I use one? Which licence do I need? Don’t worry, we’ll be answering all your questions right here.

Shall we start with the what?

What is stock photography?

Stock photography (or stock photos) refers to images that are licensed to buyers based on the intended usage. They’re usually uploaded to a stock library where users can search for images based on keywords.

But what’s important to note is that the photographer still owns the copyright to the image. The purchased licence simply serves as formal permission to use an image for the specified use.

Stock photos are licensed to buyers based on the intended usage. The photographer still owns the copyright. Purchased licences simply serve as formal permission to use an image for the specified use.

Why use stock photos?

Stock photos are used because they’re cheaper and faster than booking a bespoke photoshoot. Furthermore, stock libraries can provide an abundance of choice to ensure you can find the perfect picture.

There aren’t many alternatives to buying stock photos either. Your only real option is paying for your own bespoke photoshoot which comes with a bunch of headaches. Not only is there a time and cost implication to this, but you’ll also have to sort out the licencing agreement which is something that stock libraries have optimised into an easy, seamless experience. And even if you do get everything sorted, the whole day can be completely ruined by the weather.

So before you do anything, it’s always worth checking if a stock photo library has what you’re after. This way, you’ll also be able to see if the chosen image works in your mock-ups. And if you’re looking for archival imagery, then stock photography is often your only option.

In summary, these are just some of the reasons why you’d use stock photos:

- Cheaper than a bespoke photoshoot

- Faster than doing it yourself

- High-resolution quality suitable for printing

- Seemingly unlimited choice

- Peace of mind regarding any legal concerns

- Easier to get the right licence

- Constantly updated

- Useful for mock-ups to check if the picture you chose works for you or your client

- Some libraries have additional services like picture research

What can I use stock photos for?

Stock photos are used in a vast variety of ways and in great numbers. Chances are, you’ve seen one today. Libraries have been building their stock photo collections over decades and here at Alamy, we have well over 220 million images available for licence. This means that whatever you’re looking for, a stock photo agency probably has it.

The use cases are broad and practically limitless. We can’t list every single example, but stock photos can used for:

- Any commercial purpose

- Websites

- Social media

- Books, magazines, newspapers and any other form of print publication

- Advertising

- Marketing

- Videos

- Set designs

- Consumer goods such as calendars

- Blogs and any other form of digital publication

- Design work

- Personal use such as wall art

- PowerPoint presentations

- Artists who may need a reference image

Where can I buy stock photos?

You can buy stock photos from any stock photo library or agency. There’s a lot of choice out there and new agencies seem to pop up every year. Some have even experimented with the idea of taking commissions through their platform and asking their contributors to fill those briefs so clients can get bespoke images. It’s a sort of halfway house between fully bespoke work and a traditional stock photo agency.

There are some specialist libraries out there – many of whom distribute on Alamy – and if you’re a specialist publication, it’s likely you already know one and have a relationship with them. But in most cases, stock photo agencies are trying to be generalists and cover a wide range of photo needs. Although the way each one tries to achieve this is different.

At Alamy, we have the world’s most diverse stock photo library by working with specialists who provide us with niche pictures while also covering an eclectic array of lifestyle images and everything in between. We can achieve this global reach as we have over 170,000 photographers and illustrators from all over the world uploading to our library while ensuring the images are authentic to their locale. If you need a specific image, it’s likely we’ll have it.

The other big consideration is price. This has traditionally been broken up into three sections: macrostock, midstock and microstock. But as the lines are so blurred between them, I’ll be combining macrostock and midstock.

Macrostock & Midstock

Macrostock is considered traditional stock photography where the images are more likely to be exclusive and command a higher price. Whereas midstock attempts to strike a balance between price and quality. There should be the option of exclusive and non-exclusive imagery at this price range too.

Microstock

Microstock is a popular option as it boasts a huge number of images at cheap prices. This means the licences for them are typically royalty-free. The model exploded with the advent of the internet as file transfers became quicker and easier. If exclusivity is a necessity for you though, then you need to be aware that microstock images are likely being sold by other libraries too and therefore more likely to be in use already.

How to search for stock photos?

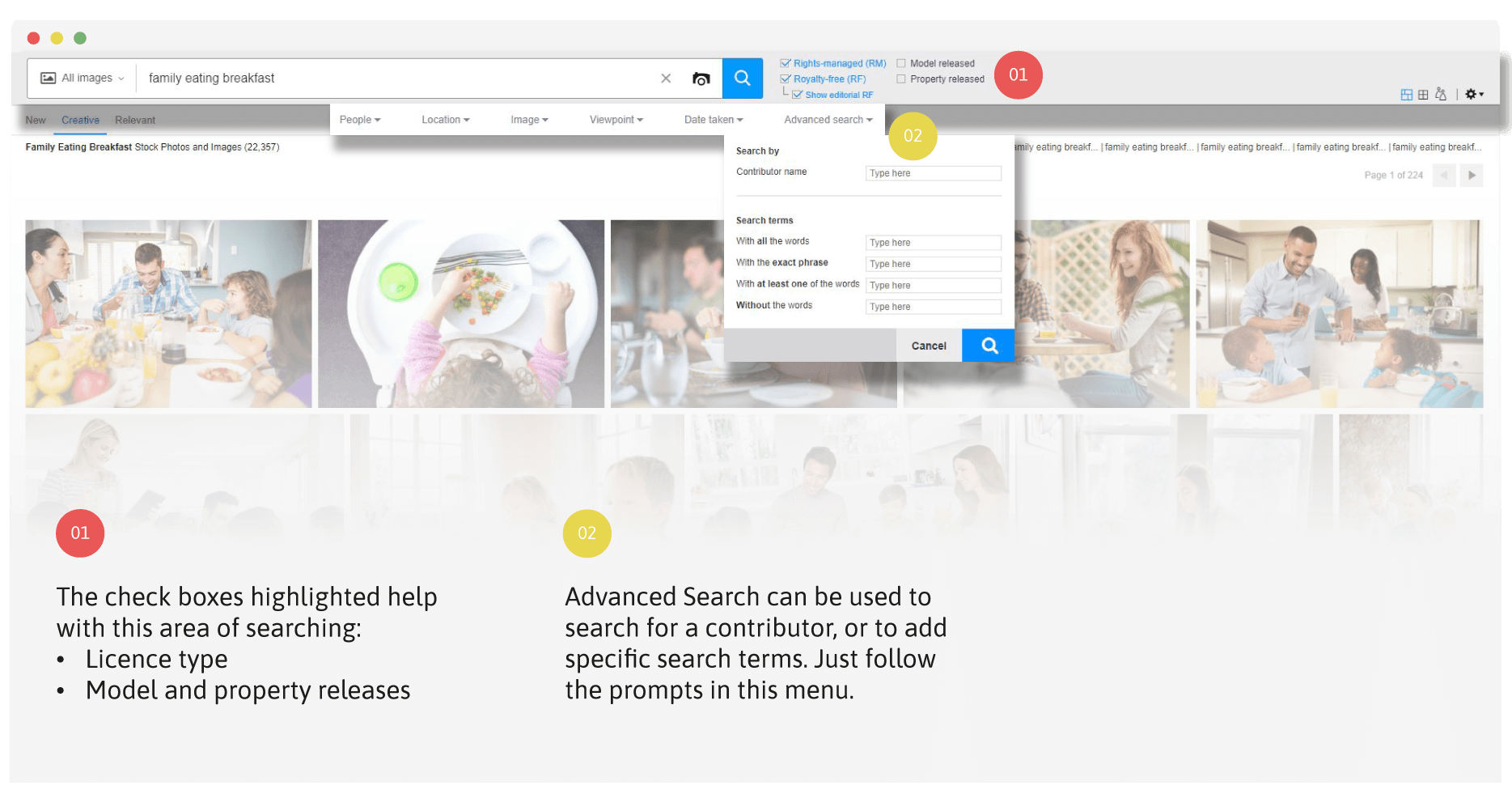

The best way to find high quality stock photos is through stock photo libraries. Although features may vary from library to library, the way you search for images is broadly the same. You’ll be reliant on the modern art of search terms.

Most search engines have some advanced search queries that allow you to exclude certain words or find exact phrases. On the Alamy library, you can find these extra features at the top of the search results page under ‘Advanced search’. But if you know your Google Search shortcuts, most of those will work too such as using double quote marks (e.g. “house of cards”) to search for an exact phrase. Otherwise, you might get results of houses and cards all mixed in.

For more help on searching for stock photos, check out our search tips guide. And if you need more inspiration, then check out the best ways to find images.

Along with the features that help you refine your search terms, there are also filters to help you specify how the image looks. Here’s a small sample of them and how they can be used:

- Refine the number of people in your imagery so you can make use of design best practice such as the rule of odds

- Refine the ethnicity of the people in your image so you can make it localised

- Filter by colour so that your campaign can be more visually coherent

- Filter by cut-outs if you’re planning on making a composite image

- Refine the date the image was taken if you’re looking for something time-specific

Although filters can help you refine your results, they can’t help you define what you’re looking for. When searching for high quality stock photos, it’s important to develop a brief to inform your search queries.

This is especially important if you’re looking for abstract concepts. In these cases, there are two ways to help you get more results to choose from. The first way would be to simply use synonyms. Let’s say you’re searching for something that conveys ‘tranquility’. Then you may also want to try separate searches for ‘calmness’, ‘relaxation’, ‘stillness’, ‘serenity’ or ‘peacefulness’.

The second way would be to convert your abstract concepts into something more concrete and tangible. For example, you may search for ‘beach’, ‘mountains’ or ‘countryside’ as these are concrete nouns that convey the idea of tranquillity.

How do I know if a picture is right for me?

This depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your image. In many cases, it could just be about whether the image is an accurate representation or not. For example, let’s say you need a picture of the Golden Bridge in San Francisco to illustrate your book about bridges. In this case, it’s probably more important that the bridge is clearly and accurately shown, as opposed to using an image that was shot more creatively from a peculiar angle, which may make an interesting image but identifying the bridge could be difficult.

Here’s a short, non-exhaustive list of things to consider when looking for an image:

- Brand – Does the image reflect your brand?

- Placement – Is it for print or digital? Do you need a landscape or portrait image?

- Copy space – Do you need it? Does the image lend itself well to copy space? (Simply having space for copy isn’t necessarily good enough)

- Localisation – Your image should be reflective of the region it’s being placed in or the audience you’re trying to reach

- Need something that’s aesthetically pleasing in a technical and objective way? – Consider the rule of odds, geometry of the composition, and flow of the image

What’s the difference between royalty-free (RF) and rights-managed (RM)?

RF image licences are broad and don’t have any restrictions besides the size of the image. They offer great flexibility as they can be used multiple times across different projects without incurring any extra costs.

You simply choose the image size you need and away you go! You can now use that image anywhere you want, however many times you want. This versatility is what makes RF images so popular today.

Furthermore, if you think you’ll be using the image in multiple places but not sure where or when, then RF images give you freedom as you don’t have to commit to any licensing decisions besides the image size.

RM image licences, on the other hand, require you to specify exactly how, where, and for how long you’ll be using any particular image. So the licence agreement is much more specific and if you discover that you need to use it in another way that isn’t specified in the licence, then you’ll need to get a new one.

At this point, you may be wondering why anyone would ever use an RM image and certainly, most people do prefer the easier-to-navigate RF images. But there are some very good reasons for why you should consider an RM image.

RF licences

- Broad

- Flexible

- Can be used multiple times

- Can be used across different projects

- Price is only dictated by image size

RM licences

- Licence agreement is very specific

- Images can be more unique

- Price adjusted for usage

- Easier to secure exclusivity

RM images are efficiently priced due to how specific the licence is. Furthermore, as RF images are now so abundant and can often be found in multiple stock libraries, RM images tend to be more unique. If you ever feel like you’ve been looking at the same images, then narrowing your search to RM could result in options you’ve not seen yet.

Due to the ubiquity of RF images, securing exclusive rights for them can be quite difficult although it is possible with Alamy. If you do need to secure exclusive rights for your glossy advertising campaign, it’s easier to do so with an RM image.

Some libraries provide bundled licences which are like hybrids of RM and RF licences. At Alamy, we do this with popular pricing. They have the benefits of RF where you can use them forever and as many times as you like, but the type of use is specified so the price is better optimised. It really is the best of both worlds!

Do I need a commercial or an editorial licence?

This will depend on your usage. But first, let’s define what each term means as that will help you understand which type of licence you need.

Editorial relates to content from a publication that seeks to impart information or to communicate an opinion; it’s essentially non-fiction. It documents real-life and current affairs although content about history is also editorial.

Whereas commercial is broadly categorised as anything that intends to monetise or sell something. This might be images in a calendar, graphics in a marketing campaign or maybe it’s a photo for your commercial website.

This may all sound quite simple so far: if I’m a publication, my material is editorial; if I’m a corporate business, my material is commercial. Not quite. A publication would need a commercial licence if it’s putting out content promoting itself as a brand. For example, if a publication is sending out collateral to promote ad space on their website, this would be considered commercial work and any images used in it will need a commercial licence.

And conversely, a corporate brand can use an editorial licence if it’s for their blog, but they must ensure the content is imparting information as opposed to selling a product no matter how subtle it is. A newsletter could also be considered editorial too as long as the content doesn’t intend to persuade people to purchase your products.

Editorial relates to content from a publication that seeks to impart information or to communicate an opinion, whereas commercial can be broadly categorised as anything that intends to monetise or sell something.

At this point, you might be wondering why it even matters. Surely, an image is an image. Yes, but you’re not buying the image, you’re buying a licence which serves as formal permission for you to use the image within the restrictions that are set by the licence.

In some cases, certain images are only available for editorial use only. This may be because it has branding on it or it may simply be a restriction set by the photographer as it’s a press picture. Furthermore, you’ll need to ensure your image has the necessary model or property releases if you want to use it commercially. So let’s go through releases now.

What is a model release and do I need one?

A model release is a document signed by the subject of a photograph saying that the image can be used commercially.

If your image has any identifiable people in it, then it will need to be model released. You don’t need model releases to use images editorially. Furthermore, you may not need a model release if the subject can’t be recognised either because their face is obscured, or their back is turned.

However, it’s a grey area because that person could argue it was them due to their clothing, haircut, body markings or being at that particular location. That’s why we always recommend ensuring your commercial images are model released when people are identifiable.

There are some rare examples where you may need to get additional clearances and indemnities. For example, there are personality rights to consider. This is the right of an individual to control how their identity is used commercially – such as their likeness. It’s generally considered a property right as opposed to a personal right, and therefore, can endure beyond the death of the individual. This is typically to protect celebrities from having their face used by brands without their permission.

Releases are only needed for commercial licences. You do not need a release for editorial licences. Remember, property releases are needed for anything that is copyrighted or trademarked. Essentially, any intellectual property.

What is a property release and do I need one?

A property release is a document signed by the owner of the property in question stating that the picture, which shows their property, can be used commercially.

Like model releases, you don’t need a property release for editorial licences. If the image contains recognisable property, then you will need a property release. Property is not just limited to buildings though; it’s anything identifiable and copyrighted or trademarked such as logos, designs, works of art, branded items, even graffiti! Essentially, anything that is an intellectual property.

If your image does have property in it but the image doesn’t have the relevant releases, then you’ll need to get in touch with the property owner to ensure you’re legally covered to use it. This includes any branding that shows up in the background of an image.

However, this often does not apply for public buildings such as government property. And like model releases, if the property is not identifiable in the image, then a release is not necessary. This includes cityscapes as there isn’t a focus on any particular building.

If you need help getting clearances, or any other assurances such as indemnification, please do get in touch and we will help you with that.

How does pricing work with stock photos?

In most cases, your needs will be covered by our popular licences. These are flexible, hybrid licences that are restricted to some of the most common image uses but have the benefits of RF where you can use them however many times you like.

If they don’t cover your needs, the price will depend on whether you’re buying an RF image or an RM image. The price of RF images is based on image size; that’s it, nice and straight-forward.

RF licence prices are based on image size. RM licence prices are based on a range of factors from placement to image use duration.

As the price of RM is suited to the licence, you’ll have to specify a few details. Fortunately, there aren’t many and everything is simple.

- Image use – How are you using the image? E.g. Is it for advertising? Is it for consumer goods?

- Details of use – If it’s for a consumer good, what type of consumer good is it for? E.g. a calendar.

- Image size – This refers to the physical size of the image as it will appear on a page, packaging or whatever it is that you’ll be printing it on.

- Print run – How many copies are you printing? If it’s for an advert in a magazine spread, it refers to how many magazines will be printed. If it’s for a mug, it means: how many mugs are you making?

- Inserts – This is for when your image is being used in an insert for a magazine or newspaper and refers to the number of times the advert is appearing in a publication.

- Placement – Where exactly is your image being placed? Images on a front cover cost more than an inside placement.

- Start date, duration and region – When will you be first using the image? How long do you need it for? And in which countries will it be used?

Not all these details are needed for every type of usage, but it shows the kind of information you’ll need to set up your RM licence.

How can I get the most out of Alamy?

We always recommend creating an account so that you can make use of more streamlined payment options but it also allows our customer service team to help you more easily as we’d be able to see your downloads and licence history.

We also offer the option of self-serving with a guest account, and this certainly makes sense if you’re an infrequent buyer.

But if you’re a frequent buyer of images in large quantities, we offer pre-built Image Packs that will save you time and money. These Image Packs are made for some of the most common licences and will get you up-and-running quickly.

If you can’t find something to suit your needs, our customer service team can talk you through some options with bespoke pricing. They’d be able to help define your needs to ensure you get the best price possible.

Whatever it is you need, we’ll endeavour to find the perfect solution for you.

How should I store my stock photos?

This may seem like an odd question and for many users, it’s not relevant. You’d just keep them on your server and dig them out when you’re ready (provided it complies with your licence agreement of course).

But for some of you, when you’re buying thousands of images a month, you’re probably wondering how and where to store your images securely. If you’ve built up an archive of RF images, you’ll want to be able to find specific images within it quickly. Maybe you file by category? Or perhaps you file them by date?

What if these don’t work for you? This is where metadata becomes very useful. Alamy images already come with metadata about the image which means the search terms you used to find it in the first place are broadly available for use in the search function of your file explorer. Give it a go! Search for an image with keywords in your downloads folder.

It’s not just about being able to find your stored images though. When you’ve built up a massive archive of images, it can be a strain and a cost on your servers. If this is proving to be an annoying headache for you, there are a couple of things you can do.

You can set up an account with Alamy which will allow you to recall any previously purchased images. Or if you need something more powerful, then Alamy iQ may be the solution you’re looking for.

Alamy images already come with metadata about the image which means the search terms you used to find it in the first place are broadly available for use in the search function of your file explorer.

With Alamy iQ, there’s no need to store images anywhere as they’re stored on your account – specifically, our servers. This means iQ remembers what image licences you’ve purchased before, and therefore, the system can show you images that are available for multiple re-use. So not only do you get storage benefits, but your workflow is faster too.

Alamy iQ also records how and where your images have been used so that you can avoid awkward duplication or you can ensure that everyone in your business only uses images that are on-brand.

If Alamy iQ sounds like a service that would help you and your business perform more efficiently, don’t hesitate to contact us and we’ll get you set up. You can find out more about Alamy iQ in this video.

What file format do I need?

That depends on where you plan to use it. The first question you’ll need to answer is whether the image will be used in print or in digital. At this point, you might be wondering what difference this makes. There are a range of reasons why there’s a difference and you can learn more about file formats on our blog.

Let’s briefly tackle print formats first. Print has much higher standards of quality than digital does as the format is so much larger. This is the case more than ever now because the most common digital screen resolutions are no bigger than our hands.

When it comes to print, you need to make sure your image is set to 300 PPI (pixels per inch). Although you’ll be able to get away with 150 PPI for billboards as they’re viewed from a distance. But if you’re working with professional printers, they’ll be able to guide you through their needs to ensure your image comes out as sharp as possible.

For print, you usually need your image set to 300 PPI. For digital, your image should be set to 72 PPI.

Although digital file formats are easier to work with and aren’t generally held to the same high standards as print, there are extra considerations which aren’t factored in when it comes to print. Firstly, your digital file formats should always have lower PPI than print – usually 72 PPI.

One of the main reasons for this lower PPI is because you don’t want it to take ages for an image to load on your website. Not only is this damaging for user experience, but your Google ranking will be hurt too as it’s sapping more data than it needs. Ideally, your file sizes for web use should always be less than 500kb but less than 200kb would be even better.

Lossy file formats like JPGs are extremely popular for web images as they are very well-optimised. If you need transparency, then you’ll need to use a PNG. If you need animations, then you’ll need to use GIFs.

Sometimes, you’ll need to use a vector file format (such as EPSs or SVGs). This is especially true for critical graphics like logos. See our blog post to find out more about vector files and when to use them.

Recommended digital file formats:

- JPG

- PNG

- GIF

What file size do I need?

Your required file size will depend on whether you’re using the image for print or digital. For web use, you’re aiming for a maximum file size of 500kb. But ideally, you’d want it around 200kb for better site performance. You can achieve this in a number of ways which we’ll explain in the next section.

Things get more technical when it comes to printing your images as they require larger, sharper files. In Photoshop (or any other image editing software), you’ll be able to see exactly how big your image. If it’s not big enough, then you may need to upsize the image but there are limitations to how much bigger you can go.

For more information on file sizes, check out our help page on file sizes where you can download a PDF guide.

How do I change my file size?

You can change your file size in any image editing software, but we’ll show you how in Adobe Photoshop.

First, let’s deal with downsizing. There are a couple of ways you can do this. You can directly change the image size by going to ‘Image’ > ‘Image Size’. Here, you can choose exactly how big you want the image to be. Our images are high resolution and therefore very large. So it’s generally good practice to reduce it down so that it’s similar in size to your final destination. You can also set your PPI values here and you’ll want to change it to 72 PPI for any image you’re using on the web.

When it comes to exporting your image, Photoshop will also give you some compressions options. Compression simply takes away superfluous pixels in the image so that it looks the same but will take up much less memory. There are no real guidelines on how much you can compress your image as it’s just a case of testing your exports and ensuring you’re still happy with the sharpness of the image.

Upsizing is a slightly more technical affair and usually something you’d just leave to your artworker. But if you don’t have one of those in your business, then you can do it in Photoshop too. As with the above, you need to go to ‘Image’ > ‘Image Size and simply change the image size dimensions so that it’s bigger.

You then have a range of ‘resample’ options. These dictate how it will handle the change in pixel dimensions and different resampling options will work better for different purposes. If you don’t have an artworker to consult with, we recommend using the ‘bicubic smoother (enlargement)’ option as standard.

Upsizing images should really be a last resort in most cases as it’s better to find an image that’s big enough in the first place. Remember you can filter your search results by image size to help you do this.

Happy hunting!

We hope that answers most of your questions regarding buying stock photography. You’ll be able to catch plenty of extra resources on the Alamy blog. Don’t worry if you don’t have time to check it all the time though. Email subscribers get great content straight to their inbox; just sign up here. But we also have an experienced multi-lingual customer service team who can answer any queries you may have. Happy hunting!