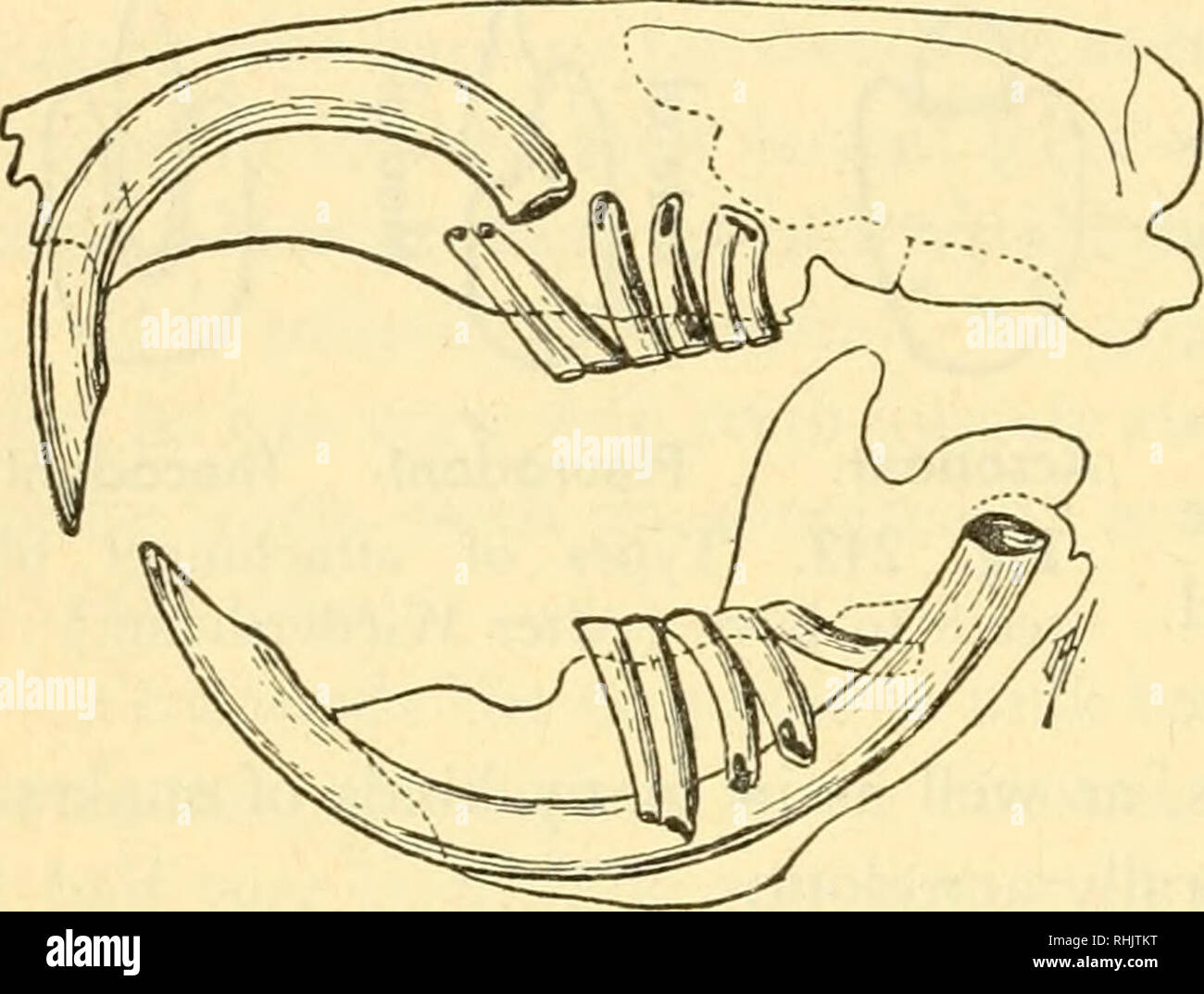

. Biology of the vertebrates : a comparative study of man and his animal allies. Vertebrates; Vertebrates -- Anatomy; Anatomy, Comparative. 294 Biology of the Vertebrates. Fig. 244. Teeth of a rodent, Geomys, showing diastema, or toothless space in jaw between incisors and molars. (After Bailey.) The incisor teeth of gnawing rodents are so deeply set in bony sockets of the jaws that they become very effective tools, as for example the in- cisors of the gopher Geomys (Fig. 244). The beaver Castor, in its engineer- ing operations, can cut down large trees with such teeth. (g) Movement.—Various t

Image details

Contributor:

Library Book Collection / Alamy Stock PhotoImage ID:

RHJTKTFile size:

7.1 MB (221.8 KB Compressed download)Releases:

Model - no | Property - noDo I need a release?Dimensions:

1817 x 1375 px | 30.8 x 23.3 cm | 12.1 x 9.2 inches | 150dpiMore information:

This image is a public domain image, which means either that copyright has expired in the image or the copyright holder has waived their copyright. Alamy charges you a fee for access to the high resolution copy of the image.

This image could have imperfections as it’s either historical or reportage.

. Biology of the vertebrates : a comparative study of man and his animal allies. Vertebrates; Vertebrates -- Anatomy; Anatomy, Comparative. 294 Biology of the Vertebrates. Fig. 244. Teeth of a rodent, Geomys, showing diastema, or toothless space in jaw between incisors and molars. (After Bailey.) The incisor teeth of gnawing rodents are so deeply set in bony sockets of the jaws that they become very effective tools, as for example the in- cisors of the gopher Geomys (Fig. 244). The beaver Castor, in its engineer- ing operations, can cut down large trees with such teeth. (g) Movement.—Various types of movement for teeth set in jaws are made possible by the muscles of mastication. The commonest type is verti- cal, or orthal, movement, which consists in lifting up the lower jaw. Just as in a nutcracker, the farther back toward the angle of the jaw the work is done, the more power- ful is the effect. In carnivores the back teeth cut past each other like the blades of a pair of scissors. Ungulates which chew the cud with a sidewise mo- tion have a lateral method of jaw movement, while horses, elephants, rodents, and some other herbivorous animals practice a "fore and aft" movement. In all of these movements the effective use of the jaw involves the teeth on one side at a time, those of the opposite side being temporarily not in contact. Snakes with their sharp backward-projecting prehensile teeth use the fore and aft movement to advantage in relentlessly passing along struggling prey down the throat. In fact it works so automatically that a snake finds it difficult to eject a mouthful, once started in the proral-palinal mill. In the higher vertebrates still other modifications in the movement of the jaws may be noted. Dr. Hooton observes that "with the shortening of the canines the human stock developed certain rotary movements of mastication which may be observed in any gum-chewing stenographer." (h) Differentiation.—According to their degree of