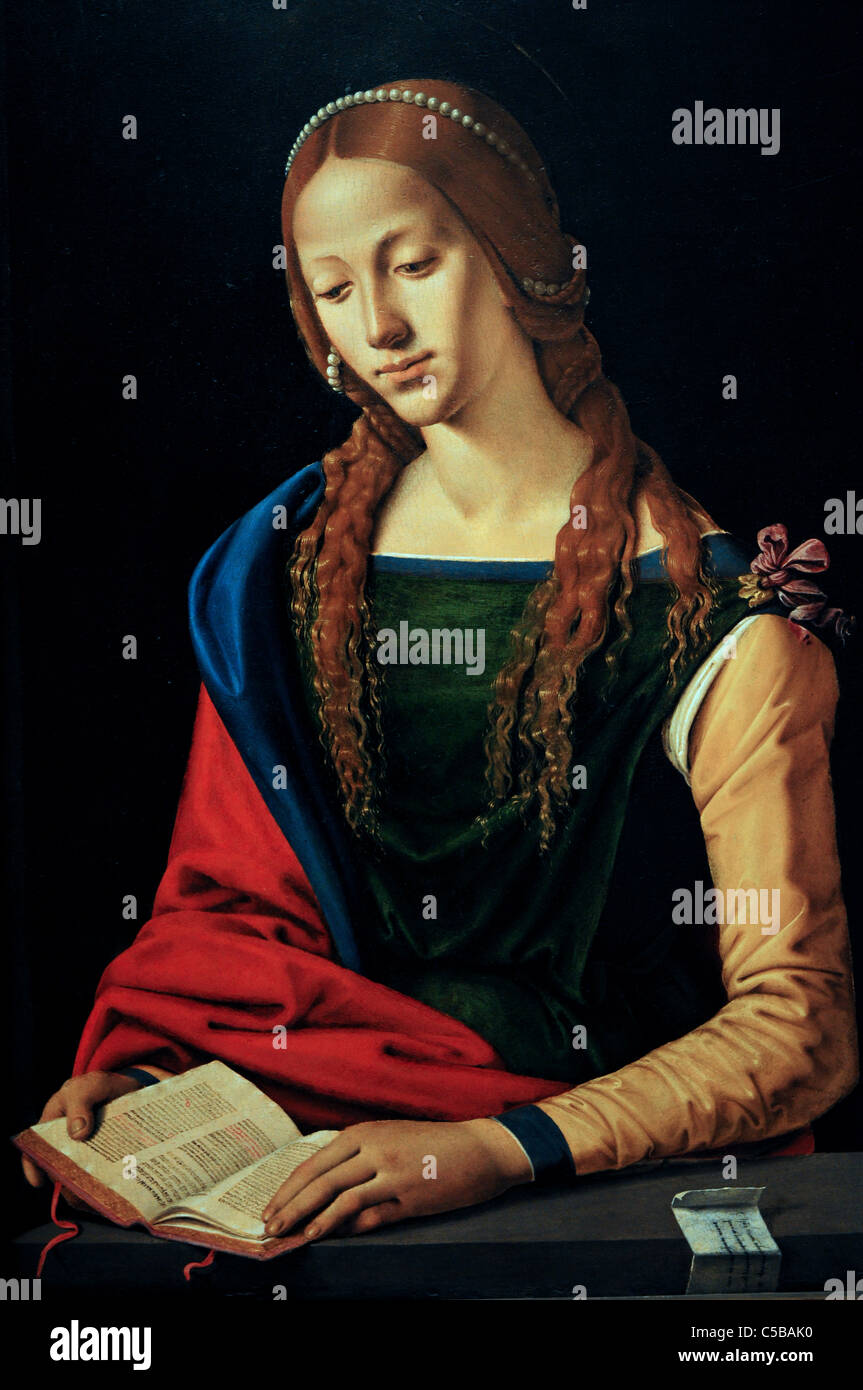

Saint Mary Magdalene reading. Piero di Cosimo. Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Image details

Contributor:

M.Flynn / Alamy Stock PhotoImage ID:

C5BAK0File size:

50.1 MB (1.8 MB Compressed download)Releases:

Model - no | Property - noDo I need a release?Dimensions:

3410 x 5134 px | 28.9 x 43.5 cm | 11.4 x 17.1 inches | 300dpiDate taken:

21 September 2010Location:

Rome, ItalyMore information:

The son of a goldsmith, Piero was born in Florence and apprenticed under the artist Cosimo Rosseli, from whom he derived his popular name and whom he assisted in the painting of the Sistine Chapel in 1481. In the first phase of his career, Piero was influenced by the Netherlandish naturalism of Hugo van der Goes, whose Portinari Triptych (now at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence) helped to lead the whole of Florentine painting into new channels. From him, most probably, Cosimo acquired the love of landscape and the intimate knowledge of the growth of flowers and of animal life. The manner of Hugo van der Goes is especially apparent in the Adoration of the Shepherds, at the Berlin Museum. He journeyed to Rome in 1482 with his master, Rosselli. He proved himself a true child of the Renaissance by depicting subjects of Classical mythology in such pictures as the Venus, Mars, and Cupid, The Death of Procris, the Perseus and Andromeda series, at the Uffizi, and many others. Inspired to the Vitruvius' account of the evolution of man, Piero's mythical compositions show the bizarre presence of hybrid forms of men and animals, or the man learning to use fire and tools. The multitudes of nudes in these works shows the influence of Luca Signorelli on Piero's art. During his lifetime, Cosimo acquired a reputation for eccentricity—a reputation enhanced and exaggerated by later commentators such as Giorgio Vasari, who included a biography of Piero di Cosimo in his Lives of the Artists. Reportedly, he was frightened of thunderstorms, and so pyrophobic that he rarely cooked his food; he lived largely on hard-boiled eggs, which he prepared 50 at a time while boiling glue for his artworks. He also resisted any cleaning of his studio, or trimming of the fruit trees of his orchard; he lived, wrote Vasari, "more like a beast than a man".